Exploring the stark reality behind the veil of promised citizenship and the perils it conceals

Following Prime Minister Narendra Modi‘s announcement on March 11th that his government would enact the contentious Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA 2019), from that very day, an old debate over the law has erupted once again.

While Mr Modi’s adversaries lambast the CAA 2019 as a discriminatory statute, alleging it would marginalise Indian Muslims and consign them to second-class citizenship, his ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) asserts that the law exclusively intends to confer citizenship upon refugees from six non-Muslim communities hailing from neighbouring Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, who sought sanctuary in India due to religious persecution in their homelands.

Recent expressions of concern from the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) regarding the announcement of the Rules of the CAA 2019 have added weight to the debate, contending that citizenship should not be granted based on religion or belief.

Additionally, various Western human rights organisations have raised similar apprehensions about the CAA 2019.

However, amid this contentious divide lies a pivotal reality: the CAA 2019 neither relegates Muslims to second-class status nor extends citizenship to the majority of non-Muslim refugees, particularly the Bengali Hindu refugees from neighbouring Bangladesh.

The CAA 2019 happens to be the most misinterpreted and misunderstood law in the history of India, which has helped none else but Mr Modi.

Regrettably, mainstream political parties, media outlets, and Indian rights activists have failed to shed light on a crucial aspect: the CAA 2019’s underlying design to deceive millions of Bengali Hindu refugees, predominantly from the ostracised Namasudra community, who constitute a significant vote bank for the BJP in West Bengal.

To truly comprehend why the CAA 2019 diverges from the claims of both sides, one must navigate the intricate web of India’s citizenship landscape.

The legacy of disenfranchisement: CAA 2003

The genesis of the CAA 2019 can be traced back to its predecessor, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2003, introduced during the tenure of former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s BJP-led coalition government in December 2003.

Subsequently, the law was enacted by the Indian National Congress (INC)-led coalition government in December 2004.

This legislation, through the addition of section 14(A) to the Indian Citizenship Act, empowered the Union government to establish a National Register of Indian Citizens (NRIC or NRC), aimed at culling those unable to substantiate their citizenship status with legacy documents dating back to 1948.

Remarkably, neither the INC nor the Left raised objections to the NRC proposal, indicating a broad consensus on the law.

Over the ensuing decades, the ramifications of the CAA 2003 reverberated, particularly among millions of Namasudra and Matuas residing in Assam, Tripura, and West Bengal.

Despite featuring on electoral rolls, they found their citizenship status plunged into uncertainty under the CAA 2003, subjecting them to relentless harassment by authorities.

Exploiting refugee anguish: The BJP’s political strategy

In a twist of fate, after the BJP itself ensured in 2003 that the Namasudra and Matua refugees in the eastern and north-eastern states would be disenfranchised, Mr Modi extended a promise of deliverance from their plight in 2014.

During the fervent campaigning for the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, Mr Modi’s deputy and incumbent Union Home Minister Amit Shah assured Bengali Hindus of expeditious citizenship under the CAA.

Mr Shah articulated a strategic sequence: the CAA would grant citizenship to Bengali Hindu refugees, followed by the NRC’s disenfranchisement of what he termed “termites”—an allusion to a significant indigenous Bengali Muslim population labelled as “Bangladeshi infiltrators” by the BJP.

The BJP secured a resounding victory across the nation and an unprecedented 18 out of 42 seats in West Bengal, propelled by the backing of Bengali Hindu refugees, notably the Matua constituency.

The trajectory of the CAA 2019

The enactment of the CAA 2019 in December 2019 triggered nationwide protests among Muslims, who decried it as legislation poised to relegate them to second-class citizenship.

Concurrently, the Opposition accused Mr Modi of fostering communal discrimination.

Leveraging the optics of these protests, the BJP sought to solidify its support among Bengali Hindu refugees in West Bengal and Assam, framing Muslims as antagonistic to their citizenship rights.

This calculated move further exacerbated social fissures that the BJP had long sought to exploit. One of the results of this fissure was the large-scale anti-Muslim pogrom carried out by rabid Hindutva fanatics in the capital New Delhi in February 2020, amid former US president Donald Trump’s visit.

Despite the assertive stance in passing the law, the BJP refrained from notifying its rules, a procedural requirement within six months of a law’s enactment.

Initially citing COVID-19 restrictions and subsequently invoking potential law and order concerns, Mr Shah’s delay tactics left the Matuas unsettled.

Why did the Modi government delay notifying the rules for four years, if the law purportedly offered citizenship to millions of Bengali Hindu refugees who migrated from Bangladesh to India?

The crux of the matter lies in a stark reality: contrary to popular portrayal, the CAA 2019 lacks provisions to grant citizenship to millions of Bengali Hindus. Instead, it only extends this privilege to a meagre 31,313 individuals.

But why? Let us delve into an in-depth analysis of the law and its rules.

Examination of legal redress for Bengali Hindu refugees

Let’s dissect the law itself to grasp why the majority of Bengali Hindu refugees, the Namasudras, won’t qualify for Indian citizenship under the CAA 2019.

The CAA 2019 exclusively addresses refugees from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, hailing from six non-Muslim communities: Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, Sikh, Christian, and Parsi.

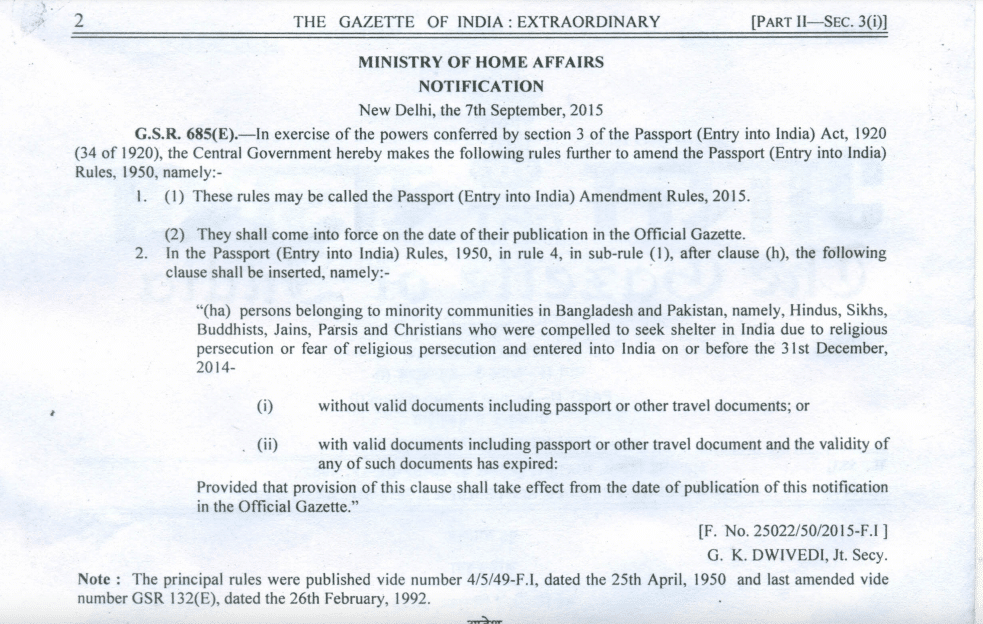

The law applies only to individuals of these religions from these three countries, who migrated to India citing “religious persecution” on or before December 31st, 2014, and were exempted through amendments made in 2015 and 2016 to the Passport (Entry into India) Rules, 1950, and the Foreigners Order, 1948.

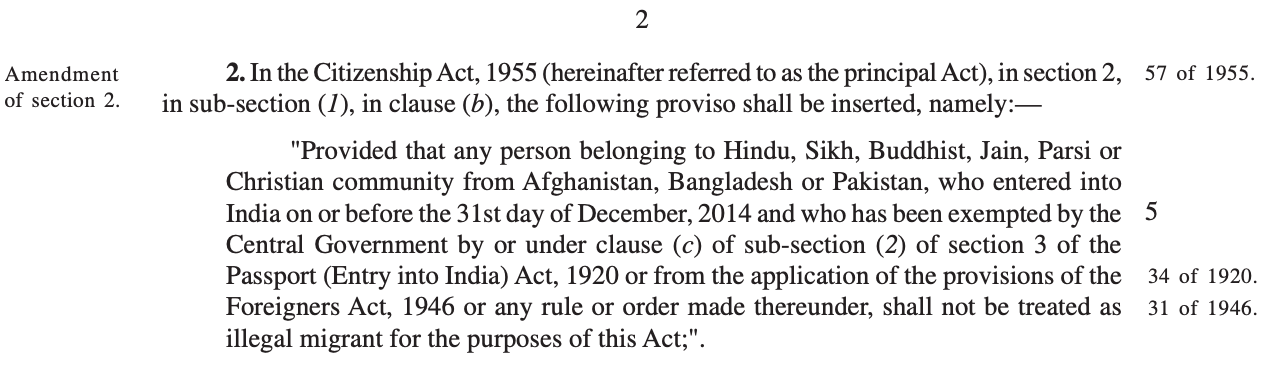

The law stipulates:

“Provided that any person belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, or Christian community from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, or Pakistan, who entered into India on or before the 31st day of December, 2014 and who has been exempted by the Central Government by or under clause (c) of sub-section (2) of section 3 of the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920 or from the application of the provisions of the Foreigners Act, 1946 or any rule or order made thereunder, shall not be treated as illegal migrant for the purposes of this Act (sic).”

Who has benefited from these amendments to the Passport (Entry into India) Rules, 1950, and the Foreigners Order, 1948?

Only individuals from the aforementioned communities who cited “religious persecution” as their reason for entering India have been exempted.

This implies that only those refugees who sought asylum or long-term visas at their nearest Foreigners Regional Registration Offices (FRRO) upon arrival in India have been exempted.

There were no pledges of additional concessions.

What’s the process for applying at an FRRO for someone who suffered religious persecution in their home country?

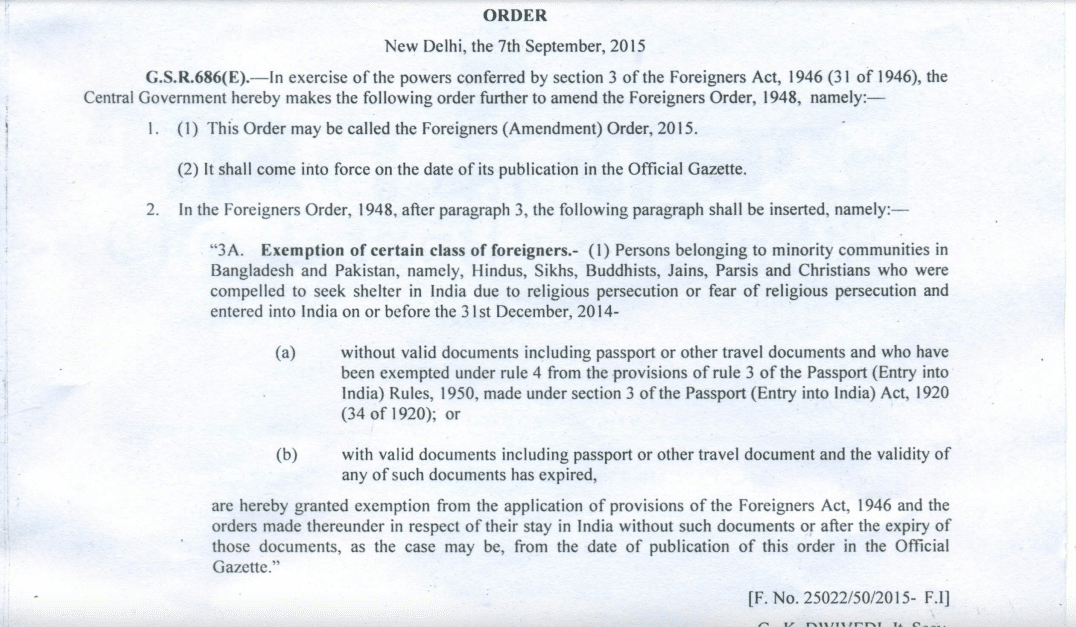

An affidavit submitted by the Intelligence Bureau (IB) on behalf of the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) before the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) reviewing the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016 (CAB 2016)—the precursor to the CAA 2019—sheds light on this process.

According to point 2.14 of the JPC report on the CAB 2016, the IB, India’s internal intelligence agency, asserted:

“As per the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) under preparation by MHA, for an applicant who applies with an affidavit mentioning that he/she was compelled to migrate to India due to religious persecution or fear of religious persecution, along with other supporting documents, a detailed enquiry will be conducted by Foreigners Regional Registration Office (FRRO)/Foreigners Registration Office (FRO) concerned to verify his/her claim. If the affidavit is not supported by documents, the case will be referred to Foreigners Tribunals to be constituted for this purpose under the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964 for verification of the claim regarding religious persecution.”

The JPC queried the MHA representative about the evidence of “religious persecution” that those seeking citizenship must submit to the FRRO for verification:

“Asked to state the mechanism available with the Government to establish religious persecution in a foreign land, the MHA responded as under: ‘Inputs from security agencies along with other corroborative evidence in the print/electronic media would help to establish religious persecution in a foreign land.’”

Here, “Inputs from security agencies” refer to Indian intelligence operatives in the respective country.

But have millions of Namasudra and Matua community members entered India through porous borders following the partition, registered with the FRRO?

The answer is no.

Contrary to assertions by Mr Modi and Mr Shah, or the BJP’s narrative, the CAA 2019 will confer citizenship rights only to 31,313 registered refugees, most likely individuals from Afghanistan and Pakistan who entered India with valid travel documents, registered themselves at the FRROs, and obtained long-term visas to reside in India.

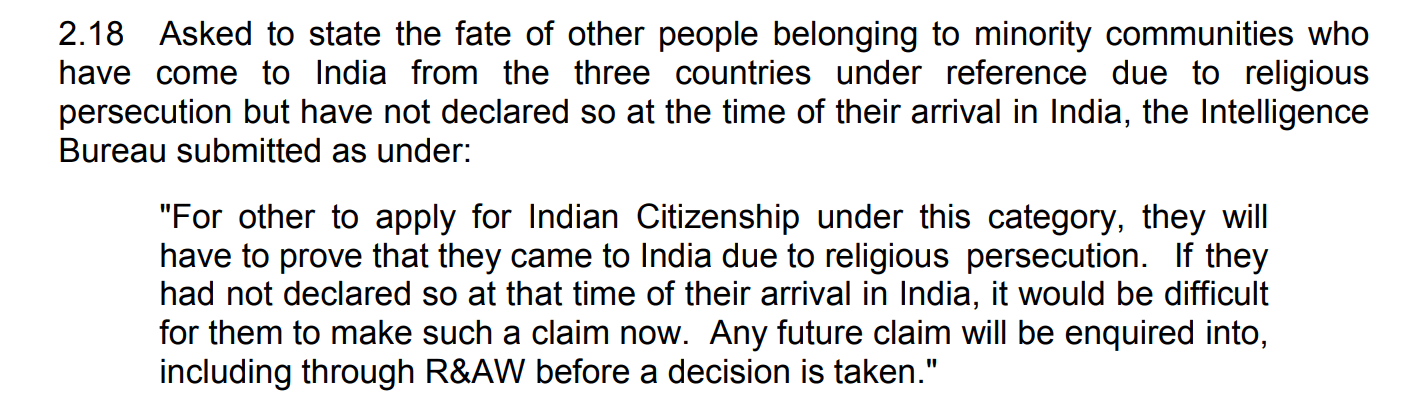

Here’s what the IB’s affidavit to the JPC states (point 2.17):

“As per our records, there are 31,313 persons belonging to minority communities (Hindus - 25447, Sikhs - 5807, Christians - 55, Buddhists - 2 and Parsis - 2) who have been given Long Term Visa on the basis of their claim of religious persecution in their respective countries and want Indian Citizenship. Hence, these persons will be immediate beneficiaries (sic).”

A Right to Information application filed by this author in 2021, seeking the actual number of Bangladeshi nationals from the six communities mentioned in the CAA 2019 who have registered “religious persecution” as the reason behind their migration to India, was declined by the IB, invoking immunity granted under this law.

This suggests that the number of Bengali Hindu beneficiaries is significantly lower than those who came from Afghanistan and Pakistan to India.

As a result, Mr Modi and Mr Shah’s administration have left these communities with scant recourse under the CAA 2019. Even if they attempt to apply for citizenship via the online portal, they are hindered by a lack of valid documentation.

Namasudras and Matuas entangled in legal quandaries

Imagine a scenario where a Namasudra or Matua endeavours to apply for Indian citizenship under the freshly promulgated Rules of the CAA 2019 via a government-prepared portal. What impediments might hinder their citizenship?

The Rules of the CAA 2019 are confined within the parameters of the law. This implies that these applicants must have been exempted under the 2015 and 2016 amendments to the Passport (Entry into India) Rules, 1950, and the Foreigners Order, 1948. This initial obstacle arises because most Bengali Hindu refugees fled erstwhile East Pakistan (or present-day Bangladesh) amid severe violence, leaving them devoid of the requisite documents for registration at the FRROs.

In contrast to the upper-caste Bengali Hindu refugees, who hailed from the privileged stratum of Bangladesh and, owing to their education and social standing, adeptly navigated paperwork in India, the ostracised Namasudras, long deprived of education and societal standing within Hindu society, struggled to procure paperwork post-partition, especially those who fled Bangladesh following the 1965 India-Pakistan war or the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War.

So, what do the Rules of the CAA 2019 stipulate?

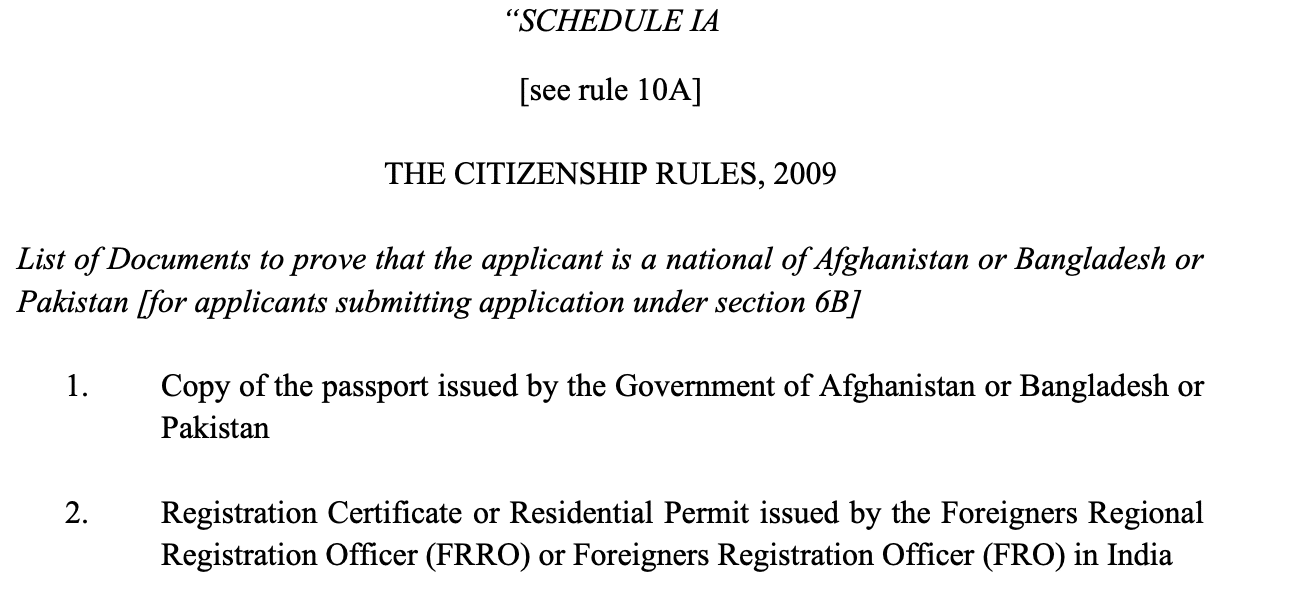

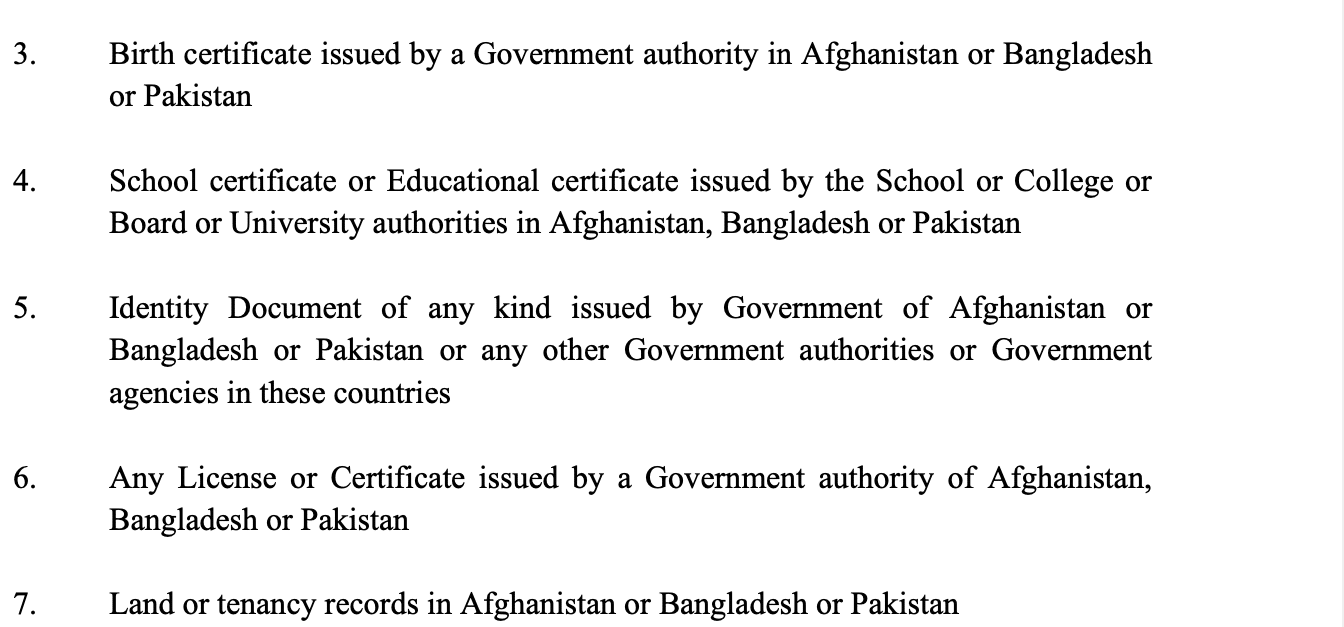

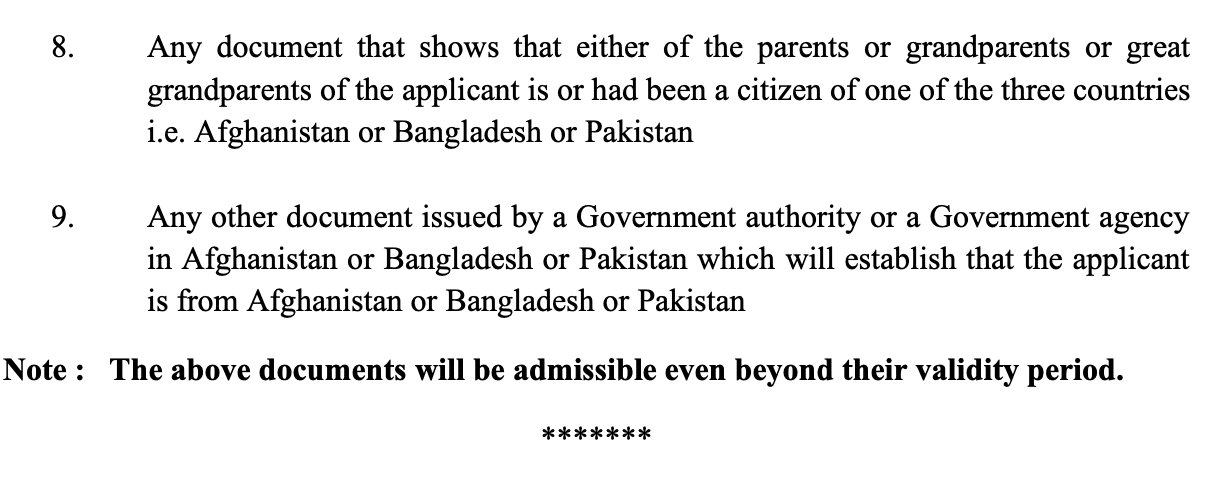

The Rules of the CAA 2019 necessitate that each application must be accompanied by one of the nine documents delineated in Schedule 1A. Herein lies the catalogue of acceptable documents according to 1A.

Furthermore, the applicant must furnish proof of residence in India using any of the documents enumerated in Schedule 1B.

An intriguing aspect arises here. The Intelligence Bureau testified before the JPC that tribunals would be established to adjudicate cases of individuals who acquired Indian documents through “fraudulent means”.

“There will be many others who might have come and they might have already taken citizenship by various means. They might have obtained a passport, ration card, and all other documents they might have obtained, and they might have already registered themselves in the voters list. So, for all practical purposes, they are already citizens of this country. Tribunals are already there to identify if any of them has obtained it by fraudulent means (sic).”

Hence, to seek citizenship under the CAA 2019, it is imperative to produce either documents from the home country or those from India, which are not fraudulently acquired. Moreover, the applicant must give an affidavit under 1C of the Rules of the CAA 2019, declaring that they have been exempted by the amendments done to the Foreigners Order, 1948, and Passport (Entry into India) Rules, 1950, in 2015 and 2016 respectively.

Consequently, individuals who migrated to India years ago due to “religious persecution” but failed to register at the FRROs due to insufficient evidence and documents, and subsequently acquired all necessary documents, may not only be denied citizenship due to the lack of documentation proving their citizenship in the home country but also face prosecution for “fraudulently” obtaining Indian documents.

The wavering Opposition

For too long, opposition parties have grappled with the BJP’s narrative surrounding the CAA-2019, inadvertently bolstering its efforts to consolidate Hindu votes while stoking fears among Muslims regarding the contentious law’s ramifications.

Even though the law does not revoke the citizenship of Muslims nor singles out the community for the threat of an NRC, it has been portrayed as an “anti-Muslim” measure, igniting fervent protests by Muslims in December 2019.

The Opposition, spanning from left to right, rallied behind this anti-CAA movement, clamouring for the annulment of the CAA 2019 while remaining notably silent on the matter of the CAA 2003.

This selective outcry, predicated on a misinterpretation of the law, inadvertently played into the hands of the BJP. Mr Modi and Mr Shah managed to convince vulnerable Namasudra and Matua refugees that Muslims were opposing their citizenship rights, exploiting their latent Islamophobia, which stems from the communal violence perpetrated against religious minorities by Islamic militants in Bangladesh.

This manoeuvre aided the BJP in consolidating the Matua and Namasudra vote banks in West Bengal. However, as the Modi government procrastinated the law’s implementation by delaying the notification of the Rules of the CAA 2019, support from the Matua and Namasudra communities in West Bengal gradually waned. Even during Modi’s recent rallies in the state, fewer members of these communities were in attendance.

Consequently, it became imperative for Modi to announce the notification of the Rules of the CAA 2019. However, rather than exposing Modi’s tactics using facts and highlighting the glaring deficiencies in the law and its rules, his opponents persist in playing the “Muslim” card, inadvertently aiding the incumbent prime minister in consolidating his Hindu vote bank, particularly in West Bengal.

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee vehemently opposes the law’s implementation in the state, asserting that her government will not permit the enforcement of this “divisive law”, despite citizenship being a Union subject according to the Constitution of India.

Her staunch opponent, the left, echoes similar sentiments. The Communist Party of India (Marxist) [CPI(M)] and others have adopted a comparable stance on the CAA 2019, labelling it as discriminatory towards Muslims without acknowledging its anti-Hindu bias.

CPI(M)-led Kerala government has also declared that it won’t allow the implementation of the law in the state, which is again an unconstitutional claim, as the States are bound to implement laws that are subjects of the Union.

Mainstream media narratives further aid the BJP in solidifying its support base and portraying its opponents as “anti-Hindu”, notwithstanding the inherently anti-Hindu, anti-Dalit nature of the law, which denies citizenship rights to millions of Bengali Hindu refugees residing in the country for decades.

Ultimately, the intricate citizenship predicament facing the Namasudra and Matua communities can only be resolved through the provision of unconditional citizenship by birth or a cut-off date.

However, the Opposition has failed to effectively champion this cause, perpetuating the issue by adopting an “everyone is a citizen” stance.

As the political arena intensifies, the fate of the Namasudra and Matua communities hangs precariously in the balance. Will history repeat itself, or will they avoid falling into the BJP’s trap once more?

Tanmoy Ibrahim is a journalist who writes extensively on geopolitics and political economy. During his two-decade-long career, he has written extensively on the economic aspects behind the rise of the ultra-right forces and communalism in India. A life-long student of the dynamic praxis of geopolitics, he emphasises the need for a multipolar world with multilateral ties for a peaceful future for all.